By Nourhan Tewfik

“A year of creative struggle can lead to a cultural democratisation.”

abdellah hassak

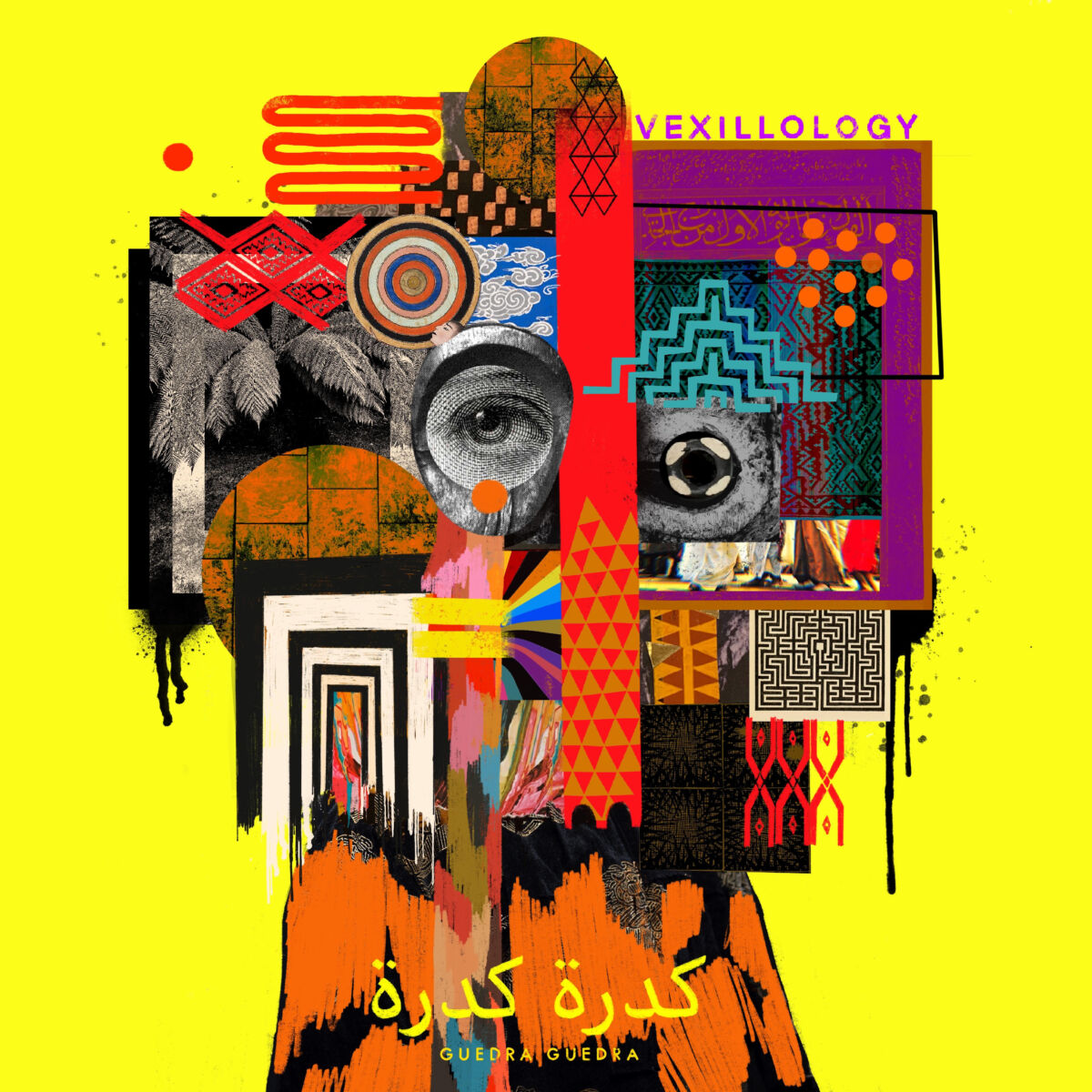

Those words mark the opening of Guedra, Guedra a 30-minute long audio performance by Moroccan sound artist Abdellah Hassak, described as “an intimate vinyl-DJ set of personal tracks and hidden gems” and performed in the artist’s own home. It is one of four performances that make up Soundclash, a two-hour long audio-visual experience curated by Toufik Douib, which premiered as part of Shubbak Festival’s music programme this summer.

Soundclash features Omar ‘El3ou’ Siakhene (Algeria), Yara Mekawei and Ahmed Mohsen Mansour (Egypt), Marwen Abouda (Tunisia), and finally, Abdellah Hassak (Morocco).

If while putting on his “first live home party in the Covid era,” Hassak is also able to question racist biases towards Sub-Saharan African and Amazigh cultures, Omar ‘El3ou’ Siakhene makes an equally important political statement in ‘Salam’, where he samples snippets of poetry and actual footage to tug at what he describes as every revolution’s “pursuit of peace.”

For their part Yara Mekawei and Ahmed Mohsen Mansour navigate the confusing reality that is brought by Covid in their ‘Space Lane’, a visual meditation on memory and time, or memory in the face of time. Finally, Marwen Abouda’s ‘Phosphene’ is a brilliant exercise in circumventing political censorship in art.

Their different projects aside, what brings these artists together are the Arab uprisings unfolding since 2011. After all, they are among a new generation of artists born out of these uprisings, who adeptly bring their political commitments into their own genre-defying sound and visual projects.

I had the chance to speak to Toufik Douib about his work on Soundclash; as well as Digi-Mena, an online mapping research platform charting artists and arts organisations in the North Africa region.

NT: At the heart of Soundclash are the political experiences of the past 10 years or so, particularly the Arab uprisings. Soundclash emerges as a response to, perhaps also a product of, a “new breed of musicians who boldly combine electronica, Dj-ing and visuals with irreverent politics.” Tell us more about the Arab revolutions as a driving force behind this new understanding of arts, and as the impetus for this project.

TD: The Arab uprisings have definitely reshaped the contemporary arts scene in North Africa. And Soundclash shows how artists in the region are inspired by, and react to, these ongoing revolutions and uprisings.

There have been many political and socio economic changes in the region, even more so in the past year. And that’s what some of the artists wanted to reflect on as well, how the experience of working as a North African sound or video artist today is more challenging, but also a more powerful tool than it was before, especially with social media now enabling artists to [release] their work online where it could be seen everywhere.

That’s what the ethos of this year’s Shubbak festival is too. Despite Covid, we chose to focus on how online digital events could be diffused, like a window or shubbak that leads to various audiences, specifically those who can’t travel and watch events happening in the UK, or those in the diaspora.

NT: Listening to Abdellah’s performance, which is effectively a living room concert, left me pondering over the remarkable adaptability of these artists. From Boumerdes and Cairo to Casablanca and Tunis, how difficult was it to work on this project, especially during a global pandemic?

TD: In the beginning, I discussed with each artist how they wanted to present their work, while being fully aware of the challenges related to Covid. Initially, Abdellah was supposed to record his performance in a venue with an actual audience, but because of Covid restrictions, we had to adapt the content. In the end, he found the experience of a home performance more intimate, and believed that it brought him closer to the audience.

Covid was also challenging for the duo in Egypt. While Yara and Ahmed are both based in Cairo, they had to work remotely. During the production, Ahmed came down with Covid, which was challenging and caused some delays in execution. But according to both Yara and Ahmed, the experience of working during Covid also brought stronger results to their work.

Omar ‘El3ou’ Siakhene also had to deal with Covid restrictions and find a way to record in Boumerdes, the cultural center of his hometown, 40 kms away from Algiers. He wanted to record in that space to [send] a message about the democratization of art, especially in Algeria where over the past year, there hasn’t been that many cultural events and with borders being closed. For Marwen Abouda, the struggle was in regards to censorship. He wanted to incorporate personal footage from demonstrations and riots that happened over the past 10 years in Tunisia. I had a discussion with him about his audience and the message behind politically engaged videos. He decided to edit the content so that no specific people or places were recognisable. It was his way of avoiding censorship while delivering strong and powerful content.

Generally, I’m always keen on bringing stories of artists living in the diaspora but also of artists based in, and inspired by, the spaces, environments and people they live with and around, in their respective cities and countries. I also enjoy working on collaborative projects. I like bringing different artists from different countries and developing a storyline to show the links between them and across the region, be they political, historical or cultural, which is something we rarely see in mainstream media.

NT: The four-part performance features mixtapes, graphics and effects. Each project is also a protest at the political as we’ve mentioned earlier. How did you originally visualise Soundclash?

TD: Initially the idea was to reflect on 10 years of the Arab Spring, and to also celebrate 10 years of Shubbak Festival. I wanted to bring new artists based in the region and interested in the evolution that has characterised digital and visual arts over the past 3 or 4 years.

For me, it was important to introduce some of these artists and give them a space on Digi-Mena, a mapping platform that I coordinate. Some of these artists had already known each other and collaborated in the past. But I was also interested in initiating collaborations between artists who had never met or worked together before.

The end result was a two-hour long film with each video being about half an hour long. The film starts with live performances, but as the production unfolds, you begin to witness more abstract and radical work, while also seeing reflections and similarities among all four projects.

NT: How has audience reception been like so far?

TD: So far we’ve received really good feedback from MENA as well as western audiences. Some imagined the performance could be shown on a big screen or as an installation in physical space. And in a way, this reception really reflects what we wanted to present—[that is to bring a sense of] closeness with the audience while also showing a bold and new mode of visual expression by artists from the region. It’s almost like a two-hour movie. You have a chance to pause or go back. If you want to watch the videos separately or watch specific parts of the performance you can also do that.

NT: Tell us more about your work at Digi-Mena. Why did you set up this mapping platform? Was your interest in connecting digital artists and organisations from the MENA region and abroad inspired by the need to contribute to their long-term sustainability?

TD: Digi-Mena was founded by Egyptian curator Ilham Khatab. We met during a workshop in 2018 and started working on this project together. As an online platform, Digi-Mena sources artists from the region or diaspora working on digital art, and aims to highlight the works of institutions that are active in, or producing, digital art. We aim to create links between artists from the region so that they are able to collaborate and work together.

It’s a big project, so we decided to split it by region. We had the pilot mapping research catalogue, which was focused on North Africa—where we sourced 40 artists from the region, some of whom are featured in Soundclash. For our next phases, we plan to focus on the Middle East and the Gulf region. We hope to be able to launch the platform’s website soon as well, so artists can subscribe for free and begin to network together. They will also be able to create events, workshops, residencies, and exhibitions together, once we are able to physically open things again, hopefully soon.

Soundclash is available as part of Shubbak Festival 2021 until 17th July.