أن تصبح

Becoming

Listen in Arabic (subtitled in English) | الاستماع بالعربية

Haja's Story

So, my name is Haja. My father was a merchant, but he was also a free man and he loved his homeland. I was born into a very conservative family when it comes to manners and good behavior, and very open when it comes to literature and poetry.

Since I was a kid, I always felt that I was supposed to have high worth. My father encouraged me, and would say that I should become President. He gave the example of Indira Gandhi, who ruled India, and Elizabeth, who ruled Britain, and then he would say: "Why shouldn’t Haja rule Sudan?" Therefore, this idea was planted in my mind. I cherished it: Haja the ruler of Sudan. It grew with me.

When I was in school, perhaps, I used to really like the literature club. I used to write poetry, short stories, song lyrics - I was able to do all this through everyone’s encouragement at home. I was also the student known for standing up for justice. I would stand up to wrongdoing at school. I was the president of the [student] union in middle school. I was very interested in theatre. I would do it all: write, produce, design, as well as play the leading role in plays. I was very dictator-like when it came to theatre, I took responsibility for everything. I really enjoyed it, from high school until the start of my college years.

The tragedy was, when I tried to make theatre and music my profession, it was refused by my community... the idea of being an actress or a singer. There had to be an alternative option for me to pursue, so I studied literature at Omdurman’s Ahlia College. To them [the community] I was studying literature, but in my mind, I was studying music and theatre. I was allowed to continue pursuing music and theatre studies but under one condition: I had to excel in every subject. I was up to the challenge.

There was a political aspect involved during those study years. I was the president of the union against Islamists from Bashir’s regime, which had ruled Sudan for thirty years. We grew up and found ourselves under the same regime, so we started resisting in secondary school. In college, resistance took another form. I was quite competent in literature. I used to always bring my sound system and encourage political debates. I was also responsible for the union’s cultural center. Until that point, everything was going well. If they arrested us, we would come out of the arrest stronger. We would speak up again, and then arrested, it was like a dual between the State Security and me. I became known amongst the state security as Haja, the political activist.

I graduated from college, and was supposed to start looking for a job. And of course, this was a tragedy in itself. There were no job offers for someone who was against the regime. So I had training in a newspaper agency and they quickly hired me and a colleague of mine. Everything was going smoothly until then. There were some arrests during my job at the newspaper, but we’d come out. That was until I met my other half- in newspapers, discussions, and in teaching. Teaching itself is another story - I, a journalist, challenged the Minister of Education, and said that he only hired people who belonged to his party. He said I should give him my CV, so I did, and was hired on the spot at the Ministry of Education.

Now I had two jobs, a journalist and a teacher. I met my other half as he worked the same two jobs. He was a political activist at the time and we had the same beliefs, except he belonged to a political party and I didn’t. We gave each other strength. The state security realised that in this house was a strong force that had to be stopped. Later the harassment started. Our honeymoon became a political trip. We were due to participate in the National Democratic Alliance in Asmara. Since we were both going anyway, we took the opportunity to take it as a political honeymoon. I was pregnant with twin girls and the harassment was intense, but we resisted, until I gave birth to the twins. It was still bearable though, the usual arrests and mistreatment. They would arrest me or my husband, and sometimes both of us. The kids would stay with the extended family. In Sudan we are known for extended families.

The tragedy began in 2003, when they arrested me when I was pregnant again. They hit me on my back and I miscarried one of the triplets. It first started with my father in law, who was really affected by this, and was even taken to the hospital. Both of us got depression. Even my father, may he rest in peace, was hit, when he spoke up to what was happening. He was hit on his kidney, and as a result his kidney failed and he needed dialysis until he died. As for my husband and I, this was the beginning of the end. He entered a state of depression; he would lose his temper at anything. Problems then started for us.

Life went on, despite the abuse and misery. It went on until 2007, when my husband got arrested and tortured. He decided to leave our family, because he felt that he could not protect us anymore. He almost forgot about me and the kids. Two years later I received the divorce papers, even though he was in a mental rehabilitation center. We consulted the Religious Council, and they said that my husband could not divorce me whilst in an unfit mental state. My husband eventually moved in with his family, and I stayed with my kids. My whole life revolved around the four kids, and how I would get them to safety.

In 2013 State Security intervened again, and I was fired from my job as a journalist. All my activities were stopped, resulting in financial issues. I moved to live in a house that belonged to a school, but the state security feared that I transmit my “deconstructive,” as they claimed, ideas to the students I was teaching. Later I moved to the teaching administration and remained a teacher without any teaching tasks. At the time there was a big opportunity for me to meet a lot of teaching staff, and we all agreed that there should be a union for teachers. A union that represents teachers, defends their rights, including their salaries, accommodation, transportation… It was the spark that we needed to start the committee for teachers. Lucky for me, and I’m proud to say, that this union was among others leading the movement in Sudan which was able to turn down Al Bashir, even after I’ve left [the union].

This marked the beginning of “things” with Al Bashir. One day when I was at school. The State Security took my kids and I away. My kids were 11 and 10 or 11 and 12. They were also taken for a while, 4 days. They were also kidnapped once. After they were kidnapped, I started thinking more seriously that we should find a way to leave Sudan. When they abused me or their father, it did not have a big impact on me, but now that they were abusing my kids I got really scared. I did not want them to go through what we went through.

After a long journey through Sudan’s cities we were able to get to Egypt. We had to cross Halfa, the Egyptian-Sudan border by foot to not be sent back to Khartoum. It was the longest, silliest, and most terrifying trip in my life. We had to walk, at night, four kids, a mother, and a guide, until we reached the Egyptian border. Once I got the passports stamped, I was the happiest person on earth. I then took the same taxi that got us to Cairo to go to the United Nations. They were really helpful, and were quick to action. They gave us a yellow card, which grants political asylum. They arranged a house and a salary for me and my kids. Life started to settle somehow, until there was a seminar and one of my friends from college found out I was in Cairo.

There was a movement similar to that of November 27th, civil disobedience and strikes. One of the things that I always used to say was: civil disobedience and strikes are the way to freedom. There was a poem that I always quoted, “No to poverty, no to oppression, no to hunger, no to all forms of poverty; with our weapon - disobedience and boycott, this chaos will fall and hardships will pass.” This poem was important to me; I don’t know who wrote it but I liked it a lot and used to repeat it a lot.

So when I came to Cairo and my friend knew I was there, she wanted me to go to a seminar in an Association called the Afro-Asian. So, I went and talked about civil disobedience and political boycott, their importance to the Sudanese people, and the fact that this was the main way to get rid of Al Bashir. After I was done with this seminar, I went home, but sensed I was being followed. I completely discarded the thought that I could be followed by state security. The next morning, on my way to dropping the kids at school, I again felt like I was being followed, and yet it did not occur to me that I could be mistreated in Egypt, especially as a refugee and a yellow card holder.

In the evening, I went out with my son Ahmed to get dinner . I was stopped by two men, probably members of the embassy security. They hit me with an electric stick on my leg and on my back. I fell on the floor. My son was yelling at them “No, not mom,” and raised his hand, which they seized and broke two of his fingers. I was on the floor, out of energy. I was really hurt. Egyptian passersby intervened and took me home. We tried to report it to the police. The first question they asked was whether I was with the embassy or the UN. When I said that I was with the UN, they told me to go to the UN for treatment. So I did. Afterwards I went to Doctors Without Borders, where I started a long journey of treatment.

This marked the beginning of events in Cairo. Right after that the UN moved us to another house. Three days later, we wake up and find our new house full of strangers. We don’t know how they got inside. There was abuse, hitting, all kinds of offence… After this incident we moved in between, three districts of Cairo for safety. Cairo, al Obour, and al Giza.

Then there was a very big attack, involving anesthetization. That was the last attack in Cairo. I don’t know how they got inside the house. I suddenly felt cold and thirsty. When I got up, I saw that all my kids and I had been attacked and were under the effect of anesthetic. Luckily my son and I recovered quickly and tried to kick them out of the house. Neighbours helped us getting everyone out.

The UN partnered with the International Organization for Migration, Save the Children, Doctors without Borders, and Care International to get us to Britain. They gave us very short notice for travelling. We were notified on the 11th and travelling was scheduled on the 14th. We were rushed out of Cairo. We arrived to the UK very tired, emotionally and physically. I am still getting treatment for various medical problems.

We got to London and felt some comfort, and safety, which is very important. We did not really appreciate the proper, clean three-story house as much as we appreciated the new sense of safety we were feeling. This was reflected mostly in the kids. They resumed their education properly and we made many friends - Barbara, Gwena, Rosemary. They visit us regularly and create a good atmosphere. Now I go to college and the kids to school.

Life is starting to go well, except for the fact that my mother is still in Sudan. She gets questioned about me. Things got a bit better after the revolution, except that the kids’ father was in prison. He was tortured, and we would see it on the media. Those were the worst days of our lives, for us to see him like that. When we got here some of his family members claimed that I should send them money, to help pay for his treatment. When I questioned them they claimed he didn’t divorce me, and if I checked the papers I would find so.

I started looking into this matter and still am, because I’d like for us to get back together as a family. He’s a good person and also a leader in the current revolutionary movement.

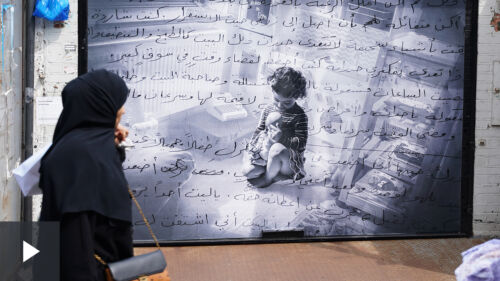

عن العمل "أن تصبح"

مشروع تركيب فني (انستاليشن) في سوق شبردز بوش بتكليف من شباك ٢٠١٩. يستقصي المشروع قضايا النزوح، الهجرة، الاندماج، العيش المشترك، الانتماء والصيرورة. الاستماع إلى تسجيلات النساء وقراءة قصصهن في الرابط أدناه (في اللغة الإنجليزية) .

للمزيد

About the work

Becoming was an installation in Shepherd’s Bush Market by artist Héla Ammar, commissioned for Shubbak 2019. The work explored questions of displacement, migration, integration, belonging and becoming. Listen to recordings of the women and read their stories using the links below.

Find out more